While current knowledge is based on new scientific understanding, historical beliefs were often influenced by what was happening in the economy and society. Let’s take a brief tour of childcare beliefs, from the late nineteenth century, to the present day.

In the 1850s, just after The Industrial Revolution, a time that saw a move towards using machinery over human hands, factories were born and so was a man named Luther Emmett Holt. Holt was an American doctor, specialising in caring for children who, in 1894, published the book, ‘The Care and Feeding of Children’. Holt was keen on routine and record-keeping and his advice echoed the more regimented and predictable machine production in industry at the time. Holt advocated all babies should be treated the same; they should be fed at specific times and should never be played with. Parents were advised to withhold affection as Holt believed this stern approach was best for the future character of the child. Holt’s theories remained popular for many years.

In 1928, ten years after the end of the First World War, the American Psychologist John B Watson took the reigns as the eminent childcare expert of the time. Watson had been heavily involved in war strategy, helping his government attempt to try to control the enemy through the power of psychology. His work during the war clearly influenced his parenting theories and his book “Psychological Care of Infant and Child” focused heavily on controlling children. Mothers were told to shake off their instinct to hug their children and instead should shake their hands. He was famously quoted as saying “If you must, kiss them once on the forehead when they say goodnight. You will soon be ashamed at the sentimental way you have been handling it." Holt advocated that babies should be left to cry, rather than responded to, so that they didn’t learn to manipulate their parents. Watson’s work certainly reduced the time parents spent with their children, perhaps affording them time to work hard rebuilding their country after the war.

The Second World War saw the next big shift in childcare ideology. British Psychologist John Bowlby became interested in the emotional wellbeing of children who had been orphaned, alongside those who had been evacuated and hospitalised. At the time, children who were hospitalised were forbidden from having visitors, even their own parents. Bowlby noticed that children suffered immensely from what he termed ‘maternal deprivation’. This spurred his work on Attachment Theory, the idea that children need free access to their primary attachment figure (usually their mother) to cope with the world. Bowlby’s ideas were further developed by both Harry Harlow, who showed it is not only human’s who need affection to survive and thrive but monkeys too, and Mary Ainsworth, who developed a method to test for attachment which is still used today. Donald Winnicott, an English Paediatrician also spoke widely about the importance of a mother’s love and affection in the early years. The tide was turned.

These child-centric theories collided with the ideal of the 1950s housewife, women who stayed home, took care of their children and made themselves and their homes look good for their working husbands. Another famous doctor, Dr Benjamin Spock, cemented the idea that women should stay home with their children.

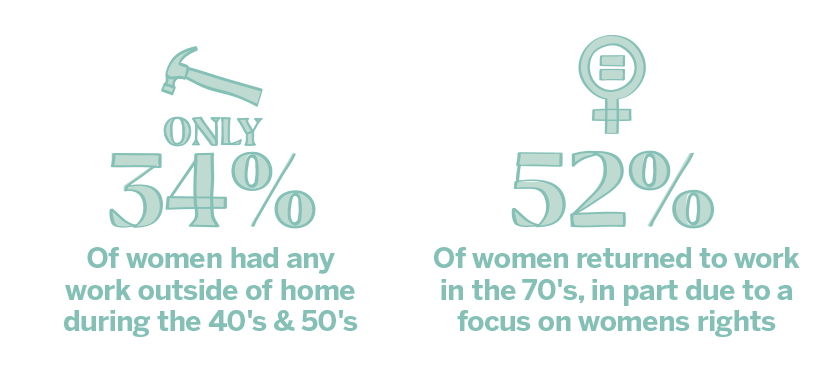

His 1946 book “Baby and Childcare” is the bestselling childcare book of all time. Women were expected to conform and very few worked outside of the home, in fact in the 1940s and 50s, only 34% of women had any work outside of the home. Men oversaw bank accounts, legal documents and household expenditure while women cooked, cleaned and took care of children.

By the 1970s, 52% of women had returned to the workplace, in part due to the ‘hippy movement’ and a strong focus on Women’s Rights. The work of Spock became unfashionable as the family became more diverse. By 1980, the number of women working hit 57%. The 1980s are infamously the decade of Thatcher, Poll Tax, Commercialism and ‘Yuppies’. As Gordon Gecko said, “The point is ladies and gentlemen that greed, for lack of a better word, is good”. In the pursuit of ‘more’, society needed to work - hard. By the end of the 1980s, almost 65% of women were in work. This trend continued through the 1990s and alongside it, a return to a more authoritarian way of child-rearing. In 1999 the childless nanny Gina Ford, published her multi-million selling ‘The Contented Little Baby Book’. Ford advocated strict routines and leaving babies to cry to get them sleeping through the night. There is undoubtedly a large cross-over between Ford’s advice and the need for children to be less bother to their busy working parents. Despite this, Ford’s ideas have been largely attacked by professional bodies for not meeting the needs of children.

The turn of the twenty first century, and the last ten years specifically, has seen another paradigm shift. Once again, parents are turning to a more compassionate way of child-rearing, akin to that of the 1940s and 50s. The driving force behind this being the development of science and the ability to prove the impact of care, via neurological imaging and ever more sophisticated psychological experiments. For instance, in 2012, research showed that Gina Ford’s Controlled Crying method does not leave babies contented, rather it left them in a heightened state of stress, albeit not communicating this distress to their parents anymore by crying. Now, with 70% of women working, a balance must be struck. Childcare is improving rapidly, as are family rights, with the introduction of shared parental leave. We know that the economy is important, as is the ability of mothers to work, but we also know that parents and children matter too. There is still work to be done, but hopefully, this time, we’ll reach a point that equally considers the needs of all and stay there.

Sarah Ockwell-Smith is the bestselling author of nine childcare books including The Gentle Parenting Book. She lives in Essex, with her husband and four children.