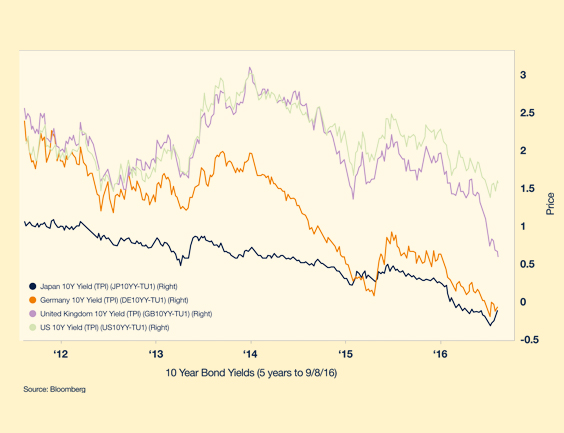

As well as the UK and US bond yields widening, the German and Japanese yields have converged to just below zero, also on the back of Quantitative Easing (QE) and other monetary stimuli.

The US / UK yield differential started to widen in May, well before the referendum result in June. No doubt Mark Carney’s pre- Brexit predictions of recessionary gloom on the back of a Brexit vote combined with polls suggesting a higher probability of a Leave outcome, led investors to presume that the chance of a Brexit vote, slower growth and lower rates for longer were more likely outcomes than before.

This line of logic was confirmed by the Leave outcome, followed by the Bank of England cutting the base rate to 0.25% and boosting QE with another £70 billion on 4th August. Having foretold recession before the Brexit vote, Carney had little room to do otherwise without losing credibility. By contrast, the US had been buoyed by the Fed talking rates higher on the back of their solid May economic data.

There seems to be something rather ironic about the UK’s decision to leave the EU being accompanied by a move in interest rates that brings us closer to Europe’s interest rate environment. But ironies aside, the big question that we have to answer is what happens next.

My own view is that pragmatism prevails as regards the UK and European negotiations and that we end up with new treaties that substantially replicate what we had before. If the UK wants to export into Europe then it will probably have to comply with European legislation, which was what we had before Brexit.

That lessens the chance of a prolonged recession, which is also aligned with Carney’s GDP forecasts which sees growth coming back to the 2.2% level by the back end of 2018.

Low interest rates are good for plugging a debt deflation spiral as you can always lend more to near-bankrupts teetering on the brink of collapse at zero interest rates; they have got nothing to lose. But lending more to consumers and companies in order to stimulate demand is a different kettle of fish. Particularly if the inefficient companies that should have gone bust in a normal interest environment block up markets and consume employment which limits economic growth. Who wants to borrow to invest for a nil-growth world? And who wants to borrow to spend more when saving what you have earned into a more uncertain world seems like a preferable choice?

It seems QE is not the free get out of jail card that central banks portrayed it as; the cost is a world where flat is the new growth.

I hope that the pound’s fall together with a pragmatic response to Brexit is enough to stimulate our economy and that the near mini-recession that Mark Carney forecasts fails to materialise. And with a stronger than expected economy the base rate cut gets reversed, which would imply that we are at or near the top of the bull market in bonds.

John Royden, Head of Fixed Income Research